One problem inherent with optical motion capture is occlusion, when a sensor is hidden from all but three cameras. This occurs when a performer passes by an obstructing object, or when the performer’s body comes between the sensor and the camera. Occlusion is impossible to avoid because no single camera angle can capture all sensors at once. Cameras cannot look through a performer’s body to find hidden sensors.

When occlusion happens, the sensor disappears from the camera’s view, and the computer has no way of knowing where it went. When occlusion ends and the sensor reappears, some optical capture systems treat the sensor as a new sensor and add a data segment at the location where the sensor reappears.

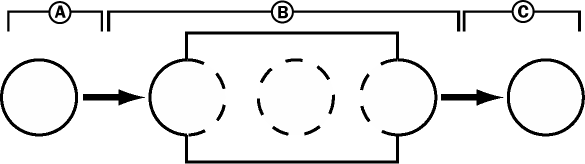

For example, let’s assume a sensor is travelling in space and becomes occluded by an object. The camera records the trajectory, as illustrated in the following graphic.

A. Sensor traveling through space B. Object obstructing the camera’s view of the sensor C. Sensor emerging from behind the obstruction

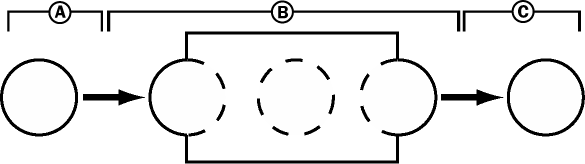

How an optical capture system may interpret the situation is shown in the following graphic.

A. Sensor’s position tracked and recorded as a segment B. Sensor can no longer be tracked C. A sensor appears and the system records a new segment

When the sensor reappears, the optical system has no way of knowing that it is the same sensor recorded as segment 1, so it begins a new data segment.

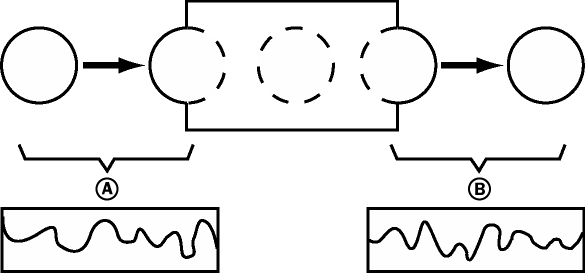

New data segment begins A. Segment 1 is recorded B. New segment is recorded using the same sensor

Therefore, the raw data capture generates a large number of disconnected data segments. It is not uncommon for a thirty-second capture session to generate hundreds of different data segments.

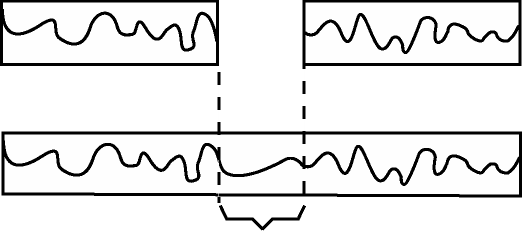

For all of this data to be of any use, all these segments have to be connected together to create continuous data for each sensor shown in the following graphic.

Connecting data segments from the same optical markers